Par Zigonet – Dimanche 2 mai 2010

Massachusetts, États-Unis – Selon les scientifiques, les individus qui rêvent d’une tâche qu’ils viennent d’effectuer sont meilleurs au réveil pour l’effectuer à nouveau que ceux qui ne dorment pas ou ne font pas de rêves liés à cette tâche.

Un groupe de 99 personnes a dû étudier un labyrinthe en trois dimensions sur un ordinateur afin de pouvoir retrouver un point de repère, un arbre. Cinq heures plus tard, chaque individu a été placé dans un autre endroit du labyrinthe virtuel. Ceux qui avaient été autorisés à faire une sieste et qui se souvenaient d’avoir rêvé du labyrinthe ont retrouvé plus rapidement l’arbre que ceux qui n’ont pas eu l’autorisation de dormir ou qui ont rêvé d’autre chose.

Selon le professeur Stickgold de l’université médicale de Harvard, qui a dirigé la recherche, les résultats mettent fin à un débat de plus de 100 ans sur la connexion entre les rêves et le cerveau. Cette étude démontrerait clairement que les rêves sont un moyen pour le cerveau « de traiter, intégrer et comprendre une nouvelle information ». Les rêves n’amélioreraient pas la mémoire mais seraient simplement le signe que le cerveau humain travaille dur pour se souvenir du chemin du labyrinthe. Le professeur Stickgold espère que des études plus poussées permettront de répondre à la question : « pourquoi rêve-t–on ?

*

Dreams Tell Us That the Brain Is Hard At Work On Memory Functions

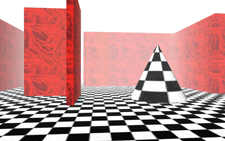

A new study in which subjects were asked to navigate this 3D computer maze is helping BIDMC scientists better understand the important roles that sleep and dreams play in memory functions and learning new information.

Date: 4/22/2010

BOSTON – It is by now well established that sleep can be an important tool when it comes to enhancing memory and learning skills. And now, a new study sheds light on the role that dreams play in this important process.

Led by scientists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), the new findings suggest that dreams may be the sleeping brain’s way of telling us that it is hard at work on the process of memory consolidation, integrating our recent experiences to help us with performance-related tasks in the short run and, in the long run, translating this material into information that will have widespread application to our lives. The study is reported in the April 22 On-line issue of Current Biology.

“What’s got us really excited, is that after nearly 100 years of debate about the function of dreams, this study tells us that dreams are the brain’s way of processing, integrating and really understanding new information,” explains senior author Robert Stickgold, PhD, Director of the Center for Sleep and Cognition at BIDMC and Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “Dreams are a clear indication that the sleeping brain is working on memories at multiple levels, including ways that will directly improve performance.”

At the outset, the authors hypothesized that dreaming about a learning experience during nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep would lead to improved performance on a hippocampus-dependent spatial memory task. (The hippocampus is a region of the brain responsible for storing spatial memory.)

To test this hypothesis, the investigators had 99 subjects spend an hour training on a “virtual maze task,” a computer exercise in which they were asked to navigate through and learn the layout of a complex 3D maze with the goal of reaching an endpoint as quickly as possible. Following this initial training, participants were assigned to either take a 90-minute nap or to engage in quiet activities but remain awake. At various times, subjects were also asked to describe what was going through their minds, or in the case of the nappers, what they had been dreaming about. Five hours after the initial exercise, the subjects were retested on the maze task.

The results were striking.

The non-nappers showed no signs of improvement on the second test – even if they had reported thinking about the maze during their rest period. Similarly, the subjects who napped, but who did not report experiencing any maze-related dreams or thoughts during their sleep period, showed little, if any, improvement. But, the nappers who described dreaming about the task showed dramatic improvement, 10 times more than that shown by those nappers who reported having no maze-related dreams.

“These dreamers described various scenarios – seeing people at checkpoints in a maze, being lost in a bat cave, or even just hearing the background music from the computer game,” explains first author Erin Wamsley, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at BIDMC and Harvard Medical School. These interpretations suggest that not only was sleep necessary to “consolidate” the information, but that the dreams were an outward reflection that the brain had been busy at work on this very task.

Of particular note, say the authors, the subjects who performed better were not more interested or motivated than the other subjects. But, they say, there was one distinct difference that was noted.

“The subjects who dreamed about the maze had done relatively poorly during training,” explains Wamsley. “Our findings suggest that if something is difficult for you, it’s more meaningful to you and the sleeping brain therefore focuses on that subject – it ‘knows’ you need to work on it to get better, and this seems to be where dreaming can be of most benefit.”

Furthermore, this memory processing was dependent on being in a sleeping state. Even when a waking subject “rehearsed and reviewed” the path of the maze in his mind, if he did not sleep, then he did not see any improvement, suggesting that there is something unique about the brain’s physiology during sleep that permits this memory processing.

“In fact,” says Stickgold, “this may be one of the main goals that led to the evolution of sleep. If you remain awake [following the test] you perform worse on the subsequent task. Your memory actually decays, no matter how much you might think about the maze.

“We’re not saying that when you learn something it is dreaming that causes you to remember it,” he adds. “Rather, it appears that when you have a new experience it sets in motion a series of parallel events that allow the brain to consolidate and process memories.”

Ultimately, say the authors, the sleeping brain seems to be accomplishing two separate functions: While the hippocampus is processing information that is readily understandable (i.e. navigating the maze), at the same time, the brain’s higher cortical areas are applying this information to an issue that is more complex and less concrete (i.e. how to navigate through a maze of job application forms).

“Our [nonconscious] brain works on the things that it deems are most important,” adds Wamsley. “Every day, we are gathering and encountering tremendous amounts of information and new experiences,” she adds. “It would seem that our dreams are asking the question, ‘How do I use this information to inform my life?’”

Study coauthors include BIDMC investigators Matthew Tucker, Joseph Benavides and Jessica Payne (currently of the University of Notre Dame).

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

BIDMC is a patient care, teaching and research affiliate of Harvard Medical School, and consistently ranks in the top four in National Institutes of Health funding among independent hospitals nationwide. BIDMC is a clinical partner of the Joslin Diabetes Center and a research partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. BIDMC is the official hospital of the Boston Red Sox.